1910-1924: Redefining Americanism

“100 Years of Welcome: Commemorating IINE’s Boston Centennial” Series:

Installment #1

The International Institute of New England is thrilled to share the first installment of our new series, “100 Years of Welcome: Commemorating IINE’s Boston Centennial.” The series will begin in 1910 and guide us to present day, chronicling the founding and growth of IINE’s Boston programming, Boston’s history as a city of immigrants, and how the two are deeply entwined. We begin during a period of record immigration in Boston—and increased backlash, as a result—as International Institutes were beginning to take shape across the country.

The “International Institute” model was an integration movement born during an immigration boom that both fueled the new factory economy in cities like Boston, and spurred debate nationwide on how newcomers should be welcomed and integrated.

A Port of Welcome

The early 1900s was a period of peak immigration to the U.S. and Boston Harbor was one of the busiest ports of entry for newcomers from around the world. Whether displaced by persecution, ravaged economies, or famine, individuals and families came to Boston for safety, freedom, and work.

By the 1910s, tens-of-thousands of people were arriving in Boston each year, and nearly 40% of the city’s population were immigrants. Already home to a large Irish community, Boston’s North, West, and South End neighborhoods filled with newly arrived Italians, Russian Jews, and Canadians, as well as smaller new communities from China, Portugal, Poland, Lithuania, the Balkans, the West Indies, and beyond.

Most people found jobs in the city’s new factories, making products like clothing and textiles, chemicals and rubber goods, or candy. Others worked as day laborers on Boston’s docks and railroads or filled construction jobs on the rapidly expanding roads, subways, and streetcar lines that gave more people access to the city and to factory jobs. Some took to selling produce or dry goods on the streets, and the most successful of these were able to earn enough to start their own grocery stores or retail shops.

Backlash and Pressure

The boom in immigration across the Northeast helped to build up cities and strengthen economies. But it also inspired fear and prejudice which worsened as the country became embroiled in the First World War. Throughout the 1910s and ‘20s, the U.S. government passed a series of discriminatory bills imposing harsh requirements for all would-be immigrants, quotas on immigration from some countries, and outright bans on others.

For organizations that worked with immigrants at the local level, a belief in the need for assimilation, or “Americanization,” became the dominant view. Immigrants were urged to shed their “old world” ways and emulate the Anglo-Protestant majority. This was the “melting pot” ideal in which immigrant cultures would melt away and be replaced by a superior American culture. A popular slogan during the war became: “100% Americanism.”

But a movement led by newly forming “International Institutes” took a radically different approach.

A New Approach to Welcome

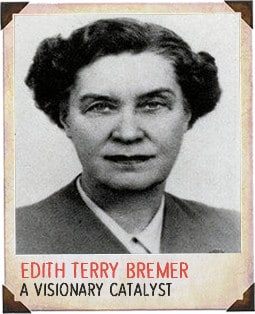

The first International Institute was established by Edith Terry Bremer in New York in 1911 under the sponsorship of the local Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), A graduate of the University of Chicago, Bremer had extensive social services experience and had worked as a Special Agent for the United States Immigration Commission. At the YWCA, she administered a survey on the status of immigrant women in the city and learned how great their needs were. In response, she founded the International Institute to provide immigrant girls and women with English language classes and recreational and club activities, and to support them with housing, employment, and citizenship.

The first International Institute was established by Edith Terry Bremer in New York in 1911 under the sponsorship of the local Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), A graduate of the University of Chicago, Bremer had extensive social services experience and had worked as a Special Agent for the United States Immigration Commission. At the YWCA, she administered a survey on the status of immigrant women in the city and learned how great their needs were. In response, she founded the International Institute to provide immigrant girls and women with English language classes and recreational and club activities, and to support them with housing, employment, and citizenship.

What set her International Institute apart was Bremer’s adoption of “Cultural Pluralism,” the philosophy that—in contrast to assimilation or “Americanization”—immigrants should be encouraged to not only preserve their cultural heritage but to share and celebrate their cultures while also participating in U.S. civic life. International Institutes became places where immigrants could continue to be themselves while learning how to navigate their new lives in the U.S.

Bremer’s model spread, and by the 1920s, 55 International Institutes opened in YWCAs in cities with large immigrant populations throughout the U.S., including the International Institute of Lowell in 1918 and the International Institute of Boston in 1924. These are the origins of the International Institute of New England of today.

Staff at International Institutes often became experts in immigration and naturalization law and served as mediators between newcomers and various government agencies. They quickly came to expand their services to work with entire families instead of only girls and women, and they often went and visited them in their homes.

The International Institutes prioritized hiring immigrants as case workers—then called “nationality workers”—who were familiar with the languages and traditions of the families they served and were often already known in their communities. An important part of implementing cultural pluralism, these staff members were usually either first- or second-generation immigrants, received training in social work, and had unique sensitivity, insight, and access into the communities they served. This practice was unique at the time and remains a priority for the International Institute of New England today.

The International Institute of Boston is Born

The International Institute of Boston was founded by Georgia Ely in 1924 at the city’s YWCA, very much in the spirit of Edith Terry Bremer and cultural pluralism. From the beginning, it was staffed with “Nationality Workers” with origins in Armenia, Greece, Syria, Russia, Poland, and Italy. Recruited from Boston’s immigrant communities, they were all college graduates with graduate-level social work training.

Speaking to immigrants in their own languages, the nationality workers helped new arrivals to access health services and educational opportunities, served as translators when needed, intervened in cases of employment discrimination, and helped people navigate the ever-changing U.S. immigration legal system and work toward citizenship.

Members of foreign women’s clubs at the International Institute of Boston enjoy skating at the YWCA gym, ca. 1924-1934. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

At the same time, nationality workers were committed to “group and community work,” helping to organize vibrant social, educational, and arts performance groups in which immigrants could explore and share their cultures. On any given night in Boston in the mid-1920s and 1930s, there might be a lecture on childcare sponsored by the South Boston Armenian’s Women Club, a play performed by a Greek youth group, or a book discussion at the South End Greek Mother’s Club. A visitor to the International Institute of Boston might encounter the Syrian Girls Club singing songs in Arabic or a performance group practicing Ukrainian folk dance and music.

As they resettled in Boston, newcomers not only found support to meet their basic needs at the International Institute, but they also found the freedom to retain their cultural identity as they built their new lives and contributed to their new communities.

Today, the International Institute of New England employs staff from over 40 countries, dedicated to continuing the practices pioneered by nationality workers over a century ago. We have seen through decades of service the value immigrants bring to our communities and our economies as they become part of us. We are excited to share their stories with you through this centennial series.

During our centennial year, we celebrate 100 years of life-changing support to refugees and immigrants in Greater Boston and prepare for our second century of service. Learn more here: IINE Boston Centennial.