1944-1953: A Home for the Displaced

“100 Years of Welcome: Commemorating IINE’s Boston Centennial” Series:

Installment #4

Welcome to the fourth installment of our series “100 Years of Welcome: Commemorating IINE’s Boston Centennial.” The previous installment, “1935-1944: ‘Don’t Condemn— Understand,’” described how the International Institute of Boston (IIB) found every opportunity available to welcome and support immigrants during the Great Depression and the Second World War, including through reintegrating Japanese Americans freed from internment.

The mid-1940s through mid-1950s were broadly a time of recovery and renewal for the New England region, and the International Institute of Boston (IIB) continued to take advantage of every new opportunity that arose to help immigrants. Boston’s economy was on an upswing, having been revived by war-time mobilization efforts. Factory jobs were coming back, and IIB advocated for fair treatment of immigrant workers in the workforce.

While prejudices and struggles persisted, national attitudes towards immigration were warming in significant ways. The U.S. had achieved victories fighting alongside foreign allies. As U.S. soldiers returned home, some brought wives from the countries they had served, whom IIB welcomed and supported. As Americans learned of the horrors oppressive regimes abroad had inflicted on their people, with time, the U.S. government opened its borders to many people throughout Europe who had been threatened, imprisoned, and displaced by the war. The International Institute of Boston worked to resettle and integrate more than 10,000 people displaced by war.

Even with these gains, however, by the early 1950s a rising fear of Communism along with continued racial and religious discrimination fueled a new batch of restrictive federal immigration laws. IIB fought against anti-immigrant legislation while continuing to reach out to new immigrant communities and holding fast to its commitment to help Boston’s immigrants preserve, share, and celebrate their cultures.

Committing to Culture

In 1944, right before the end of WWII, then governor Morris J. Tobin held a Conference on Recreation, convening leaders from throughout the Commonwealth to discuss ways to relieve wartime stress and promote understanding between cultures. The International Institute answered the call, helping to organize and sponsor a Fall Folk Festival at its former headquarters, the Boston YWCA. Over two days, 200 Bostonians gathered to witness demonstrations of folk arts and crafts, performances of lively music and dance from a wide variety of immigrant communities, African American spirituals, and traditional music and dance from the Wampanoag and Navajo tribes. The Fall Folk Festival would grow into the New England Folk Festival, which was sponsored annually by IIB for the next 25 years.

IIB took its role as a preserver and promoter of immigrants’ cultures very seriously. During this period, the Boston Council of Social Agencies conducted a study recommending that IIB discontinue its “nationality work”—which focused on strengthening immigrant communities through education and cultural activities—to focus strictly on the “technical issues” of the immigration and naturalization process. IIB protested, calling on its many allies in academia and government to submit letters in support of IIB continuing the full scope of its services. This campaign prevailed, convincing the Council to withdraw the recommendation, and IIB stayed true to its founding vision. In fact, IIB expanded its “nationality work” during this period, notably welcoming its first Black nationality group, the Liberian College Association, and convening a Chinese Club to support Boston’s Chinatown neighborhood.

Fighting for Fairness

While continuing its cultural and case work, IIB also returned to addressing workforce issues. Immigrants in Boston had long been vulnerable to exploitation in the workforce because of language barriers, prejudice, and lack of access to legal protection. From its earliest days in the 1920s, IIB mediated between immigrants and their employers to advocate for fair wages and treatment. When the U.S. government awarded Boston contracts for shipbuilding and production of ammunition and other products needed for war, many of Boston’s immigrants and their children heading back into once-shuttered factories faced exploitative conditions. In 1946, IIB successfully advocated for the Massachusetts Fair Employment Act which established the Fair Employment Practices Commission—a huge win for immigrant and all workers’ rights in Boston. The new commission could enforce laws prohibiting employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religious creed, national origin, or ancestry, and in 1950, its mandate was extended to housing and public accommodations.

IIB also continued to advocate for fairness in immigration policy at the federal level. In 1952, when Pauline Gardescu took the reins as the third Executive Secretary of the International Institute of Boston, she began her tenure by testifying before congress in opposition to the discriminatory (and ultimately adopted) racial and national origin quota proposed in the McCarran-Walter Act, which set limits by country on the number of immigrants that could be admitted into the U.S., heavily favoring those from northern and western Europe.

Welcoming “War Brides”

Many Bostonian immigrants who fought in WWII returned home to new opportunity. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, later known as the G.I. Bill of Rights, or simply the G.I. Bill, provided veterans with loan guarantees for home mortgages, money for college or vocational school, and unemployment compensation. The bill helped millions of European immigrants who had fought in the war, including many whom IIB had helped through poverty, to buy their first home in the U.S. and join its middle class.

Returning soldiers also brought home spouses from the countries in which they had served. IIB welcomed these new Bostonians, helping them with immigration legal and naturalization services, and bringing them together for mutual support in weekly convenings of an “Overseas Wives Club.” IIB furthered its work on behalf of women immigrants through advocacy, fighting for gender equality to be enshrined in the federal immigration laws of the day.

Providing Refuge to the Persecuted and Displaced

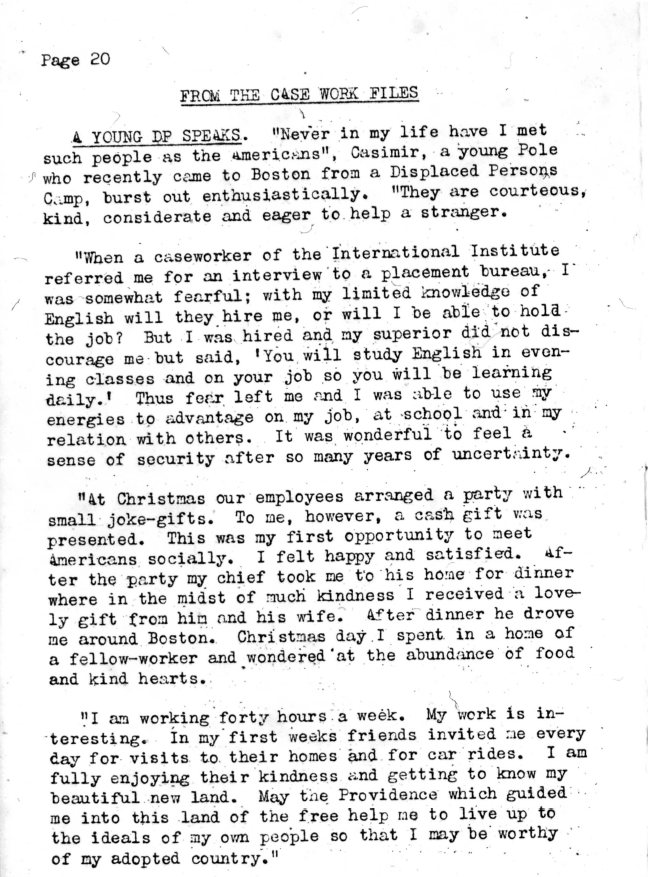

By 1948, seven million Europeans had been displaced by the war, prompting the passage of the federal Displaced Persons Act, a pivot point for U.S. immigration and the work of IIB which was further expanded in 1950 to accommodate Jews who had fled Nazi atrocities. Supported by IIB, this was the first U.S. bill aimed specifically at granting entrance to immigrants forced from their home countries and prevented from returning for fear of violence or persecution. This bill led the U.S. to admit an initial 400,000 “displaced persons” (DPs) into the United States over and above immigration quotas provided they find a place to live and a job.

Between 1948-1952, IIB led the way in resettling 10,000 Displaced Persons in Boston, sending interpreters to meet them as they arrived at Boston Harbor, finding sponsors to help more than 200 individuals with housing and employment, and providing support services. Other notable recipients of support were three so-called “Ravensbrück Rabbits,” women who had survived medical experiments in a Nazi concentration camp in Poland and came to Boston seeking reconstructive surgery under the sponsorship of a group led by journalist Norman Cousins. IIB provided these brave survivors with housing, interpretation, and financial support.

In 1951, the International Institute coordinated the “Special Project–International Refugee Organization (SPIRO)” which resettled more than forty families of displaced people who had disabilities or other challenges requiring special support. The following year, IIB expanded its English language classes to serve 2,500 Displaced People, and a two-year grant from the Ford Foundation enabled IIB to provide both English classes and job training for more than 600 refugees from Russia and the Ukraine by the end of 1953. Many of these new arrivals, along with refugees from China and Eastern Europe, were admitted under the Refugee Relief Act of 1953, which authorized visas for those fleeing communist countries.

Today, the International Institute and our supporters continue the legacy of advocating for fair immigration and employment policies and necessary resources for refugee resettlement, while working to make Boston a home for the displaced and the persecuted.

During our centennial year, we celebrate 100 years of life-changing support to refugees and immigrants in Greater Boston and prepare for our second century of service. Learn more here: IINE Boston Centennial.

Related Articles

From the Desk of the CEO: Envisioning a Better Future for Humanitarian Immigration

5 Things to Know About the Refugee Act of 1980