Tracing Our Roots: IINE Leadership on Their Families’ Journeys to the U.S.

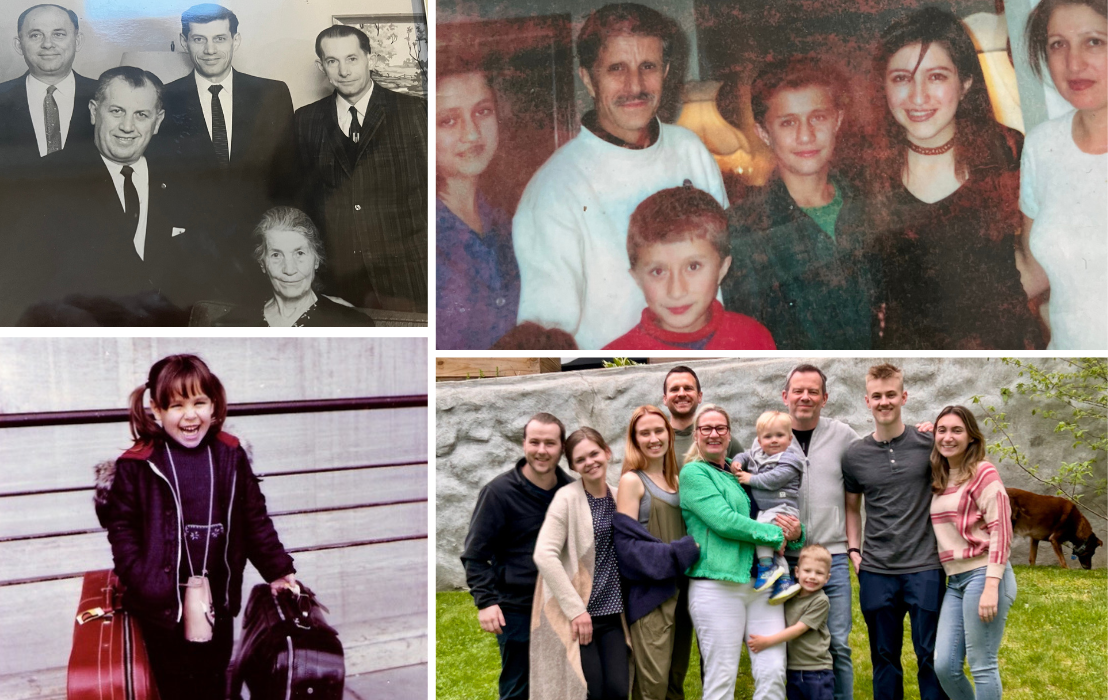

As we celebrate our Boston Centennial—100 years of welcoming and supporting refugees and immigrants—we are reminded that nearly all of us have an immigration story to share, whether we were the first in our family to build a life in the United States, or it was our parents, grandparents, or generations further back who first made the brave journey to this country.

For our blog, members of our Board of Directors and our Leadership Council share how their families came to call the U.S. home.

Carolina San Martin

Managing Director, Global Head of Sustainable Investing Research, State Street Global Advisors; Member, IINE Board of Directors

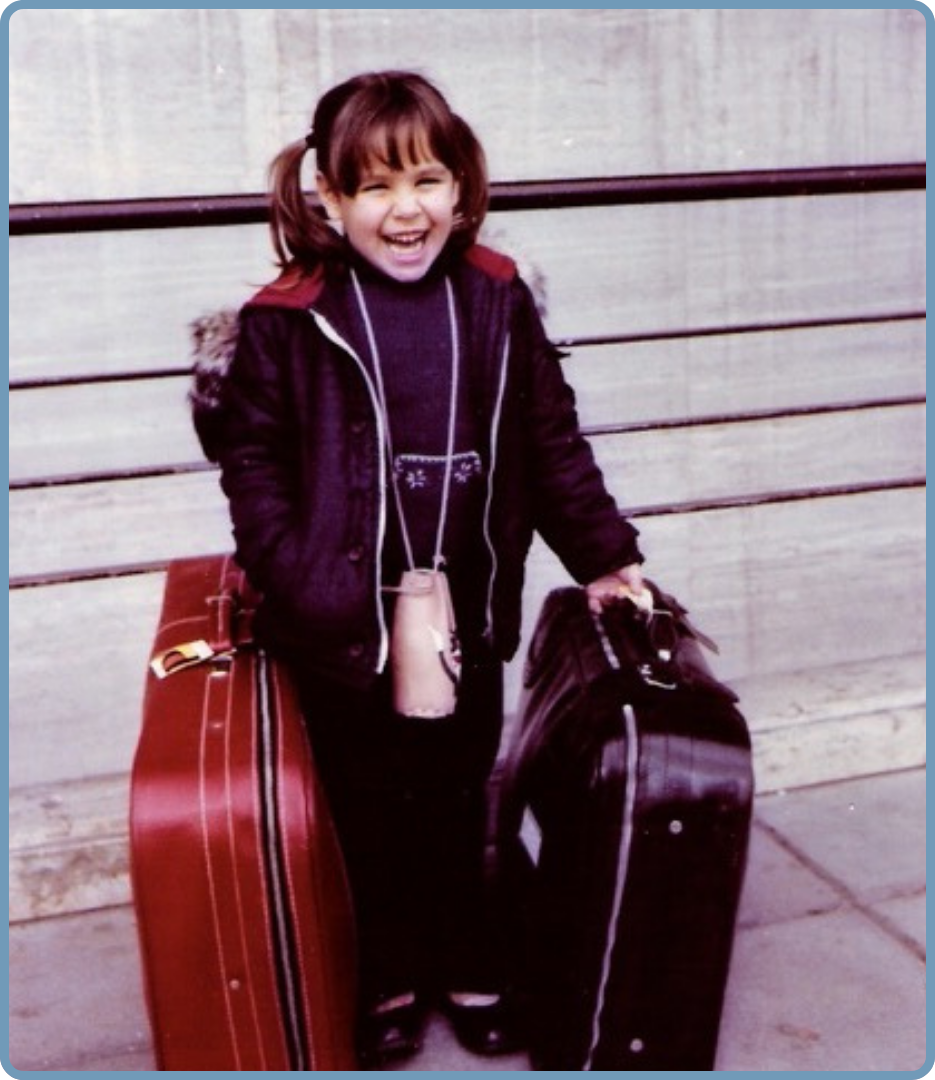

Rio de Janeiro, 1976: My mom, a young Argentine with a gift for languages, finds herself a single mother in a foreign country. As a child, she had dreamed of leaving Argentina someday, but where she dreamed of going was not Brazil, it was the United States. As unexpected and difficult as it is to be in her situation, she is now free to pursue that dream. A few years later, she gets her chance. Her strong track record in a globalizing American firm gets her a transfer to the company’s headquarters in the U.S.

Smyrna, Georgia, 1979: I find myself settling into kindergarten. I don’t speak English, no one around me speaks Spanish or Portuguese. I don’t understand what the teacher is saying or how things work, but little by little, I figure it out. At the time, I see my predicament as a handicap. I am the different one, the outsider. I experience all the reactions and insecurities one would expect of a child in that situation: when kids laugh and I don’t understand them, l wonder, Are they laughing at me? When we are learning grammar rules and writing in class, I think, How far behind am I going to be since I’m still learning English?

Boston, Massachusetts, 2025: Looking back, what I thought was an obstacle – being the immigrant who was different – was an immense gift. I understood at a young age how much I could grow by having the determination to figure things out. It was more than just adapting – I was understanding my capacity to learn and accomplish more than I seemed capable of, all thanks to being the different one in that kindergarten classroom.

Fereshtah Thornberg

Executive Vice President, Head of Sales & Client Management, North America, State Street; Member, IINE Board of Directors

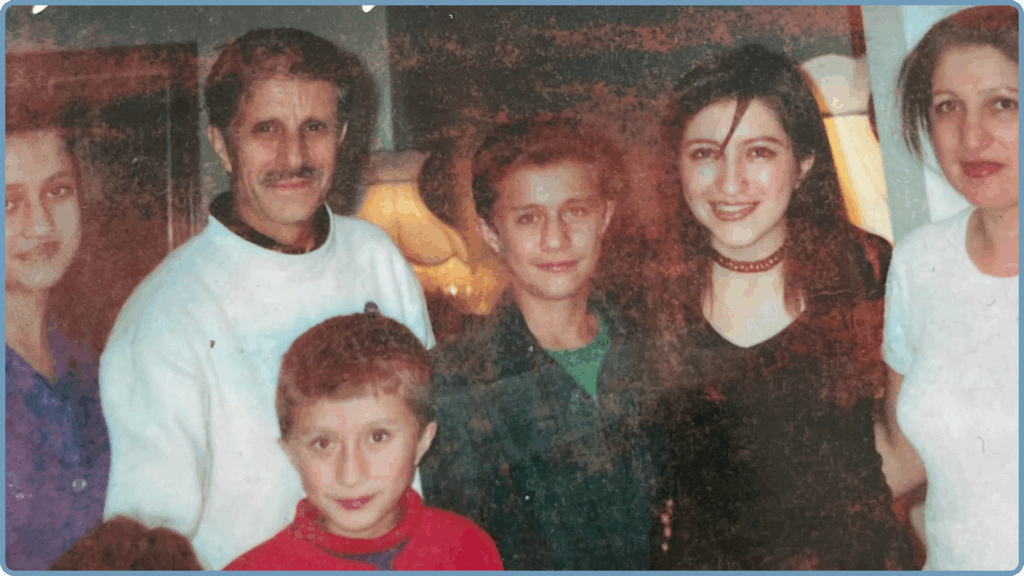

My mom, three of my siblings, and I left Kabul, Afghanistan, in 1989, heading for New Delhi. This was towards the end of the Russian invasion with growing worries around the Taliban’s influence. We migrated to New Delhi as refugees while my dad worked on finding his way out of Kabul. We lived in a single room rental in New Delhi as we settled in and worked on our next goal of settling in Europe or America. My mom started to volunteer in the refugee center and later on was hired as a full time employee. I worked on building skills that could land me a job, while remotely working on my college degree. I started with typing lessons and later on joined a program to study computer science.

Four years later, we received our green cards and flew to New York where we had family and a support system. Settling in New York was many times more challenging than New Delhi, and I often comment that I wish we had had access to an organization like the International Institute of New England. 30 years later, we live very successful fulfilling lives, and there isn’t a week when we don’t reminisce about our journey here.

Tuan Ha-Ngoc

Retired President and CEO, AVEO Oncology; Member, IINE Board of Directors

I was born and grew up in Vietnam during the Vietnam War. In 1969, I had the opportunity to leave the country to pursue higher education with the condition that after graduation, I would return to Vietnam to help build the country despite the war. I landed at Paris University, where I obtained a pharmacy degree. I had been planning to return home in the summer of 1975, when the country fell to Communist rule that April. I had two options: return and live under a Communist government or stay in Paris and seek asylum, which is what I did. I still have the document issued by UNHCR, which deemed me “stateless.” It’s a word that has stayed with me to this day. It felt like I belonged nowhere, that I was on a boat in a vast ocean by myself—not literally, of course, though many of my compatriots experienced exactly that.

Thankfully, my parents and siblings were able to leave Vietnam and join me in France. I stayed there for two years during which I obtained a Master’s Degree in Business Administration from INSEAD. In 1976, I joined a U.S. company called Baxter Healthcare, at their European HQ in Brussels. Then in 1978 two things happened—I got married to my beautiful wife, and my company decided to transfer me to its U.S. headquarters in Chicago.

We arrived there in November with very little money, no family or friends to rely upon, and with my wife speaking very little English. That’s how we started our lives in the U.S. In 1984, I was recruited by one of the first biotech companies, which brought us to Boston, where we have been ever since.

Deborah Dunsire

Chair, Neurvati Neurosciences; Former CEO, H. Lundbeck A/S; Senior Advisor, Blackstone Life Sciences; Member, IINE Leadership Council

I was born in Zimbabwe to Scottish immigrant parents, and my husband was born as the oldest in the third generation of mixed English and Netherlands families. After medical school and working as a GP and my husband as an orthopedic resident, I joined the pharmaceutical industry and was transferred to Switzerland, where my husband joined the same company. We were independently both offered jobs in the U.S. headquarters in New Jersey in 1994 and set off on our 30+ year adventure in the U.S. We quickly learned to love the open-hearted hospitality and admired the philanthropic culture that abounds here. We also learned that English is not the same all over the world!

My husband and I became naturalized U.S. citizens in 2004, and raised our two sons here.

Wade Rubinstein

Founder and President, The Bike Connector, Inc.; Member, IINE Board of Directors

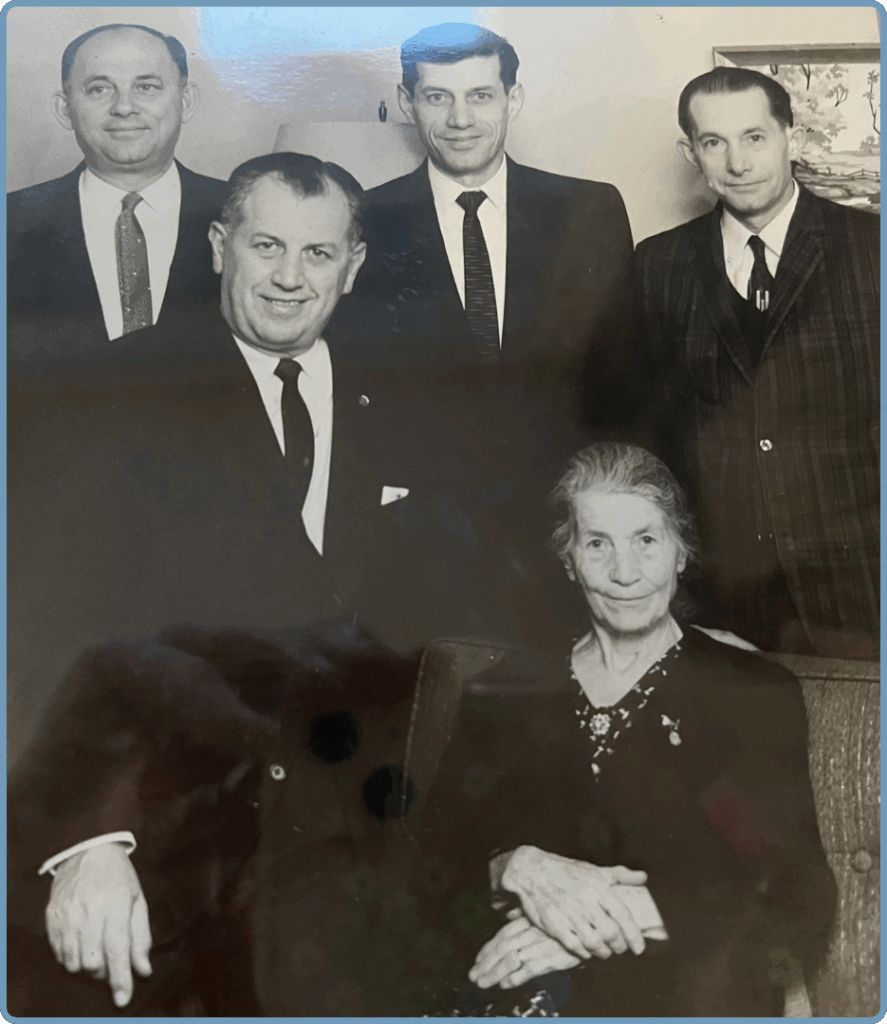

I am the son of immigrants. My mother’s family came to Boston in the 1920s after fleeing pogroms in Russia. My father, who grew up in a town that’s now part of Ukraine, was a Holocaust survivor. During the war, he was in hiding for three years. The Soviets liberated him in the spring of 1944. An orphan after the war, my dad lived in Displaced Persons camps in Czechoslovakia and Germany. He was smuggled into Palestine in 1946 and came to the U.S. as a refugee in the early 1950s to join family members who were already here.

My parents’ journeys have shaped me in a foundational way. Because of their resilience and hard work, I had the chance to become a first-generation college graduate.

I studied computer science at Boston College. After college, I worked at a Digital Equipment Corporation for 10 years, before going on to work at several telecommunications start-ups. In 2003, I left the field and pursued a degree in elementary education. I taught in West Newton for a couple of years. Then, I decided to open up an ice cream shop, Reasons to Be Cheerful, which I ran for eight years. I sold the shop in 2018 and founded The Bike Academy, which was an after-school bike riding program in Lowell and morphed into the nonprofit I run today—The Bike Connector.

I’ve always felt life is too short to not pursue your interests; it keeps things interesting! And for me, it’s felt like my opportunity to live the American Dream—which I can only do because of the choices and sacrifices my parents made.

Örn Almarsson

CEO and Co-Founder, Axelyf; Member, IINE Leadership Council

In 1989, I left my native Iceland to pursue graduate studies in the United States, marking the beginning of a remarkable scientific and personal journey. With a deep passion for chemistry and molecular science, combined with a desire to contribute positively to human health, I embarked on a Ph.D. program in bio-organic chemistry at the University of California, immersing myself in advanced research at the intersection of organic chemistry and biological sciences. My academic success and intellectual drive led me to a post-doctoral research position at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), one of the world’s leading centers for innovation in science and technology.

At MIT, I refined my expertise under the guidance of world-class scientists and engineers, and moved toward translational applications of chemistry in pharmaceuticals. It was here that I forged important scientific and professional relationships that helped launch my industry career. My first role in the pharmaceutical industry came at Merck, where I contributed to drug discovery and development in a dynamic and deep R&D environment known for scientific rigor and excellence. This position marked the start of my enduring commitment to advancing therapeutics for human health.

Over the years, my contributions have extended across multiple therapeutic areas, with one of the most notable being my work on the formulation and delivery system of Spikevax, Moderna’s mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine. My expertise in drug delivery, particularly involving lipid-based systems, played a significant role in the successful evaluation and ultimate deployment of the vaccine during a time of global crisis. In addition to this very visible achievement, I have worked on numerous other pharmaceutical products and delivery technologies that have improved patient care and therapeutic outcomes in psychiatry and treatment of infections, for example.

My journey is also one of family, partnership, and shared purpose. My wife, Brynja, also from Iceland, has been a constant presence throughout this journey, offering support and building a warm, bicultural home in the U.S. Together, we have raised three children who have each found their own path in healthcare and pharmaceuticals—continuing the legacy of scientific inquiry and public health impact that defines our family. Whether in biological research, biotechnology, or healthcare delivery and education, each member of our family contributes uniquely to the field, embodying the values of education, service, and global citizenship.

From a young Icelandic student to a scientific leader who helped shape one of the world’s most important medical interventions, my immigration story is one of dedication, resilience, and enduring impact.

Jeffrey Thielman

President and CEO, International Institute of New England

My great-grandmother, Antoinette, came from Italy to the U.S. in the early 1900s. She came over from Naples on a boat. It was an arranged marriage that brought her here. She went on to have seven children, one of whom was my mother’s father—my grandfather—who I adored and who rose to become a state senator in Connecticut.

My great-grandmother had very little money, and she never quite learned English well. She struggled a great deal to adapt and learn a new culture, but she worked very, very hard to make sure her sons and daughters were contributing citizens of our country. I am proud to honor her through my work today.

During our centennial year, we celebrate 100 years of life-changing support for refugees and immigrants in Greater Boston and prepare for our second century of service. Learn more here: IINE Boston Centennial.

Somali culture is based on hospitality. They are a joined community—a community connecting each other. They live as a family. Somali culture is based on loving each other, on welcoming people.”

Somali culture is based on hospitality. They are a joined community—a community connecting each other. They live as a family. Somali culture is based on loving each other, on welcoming people.”

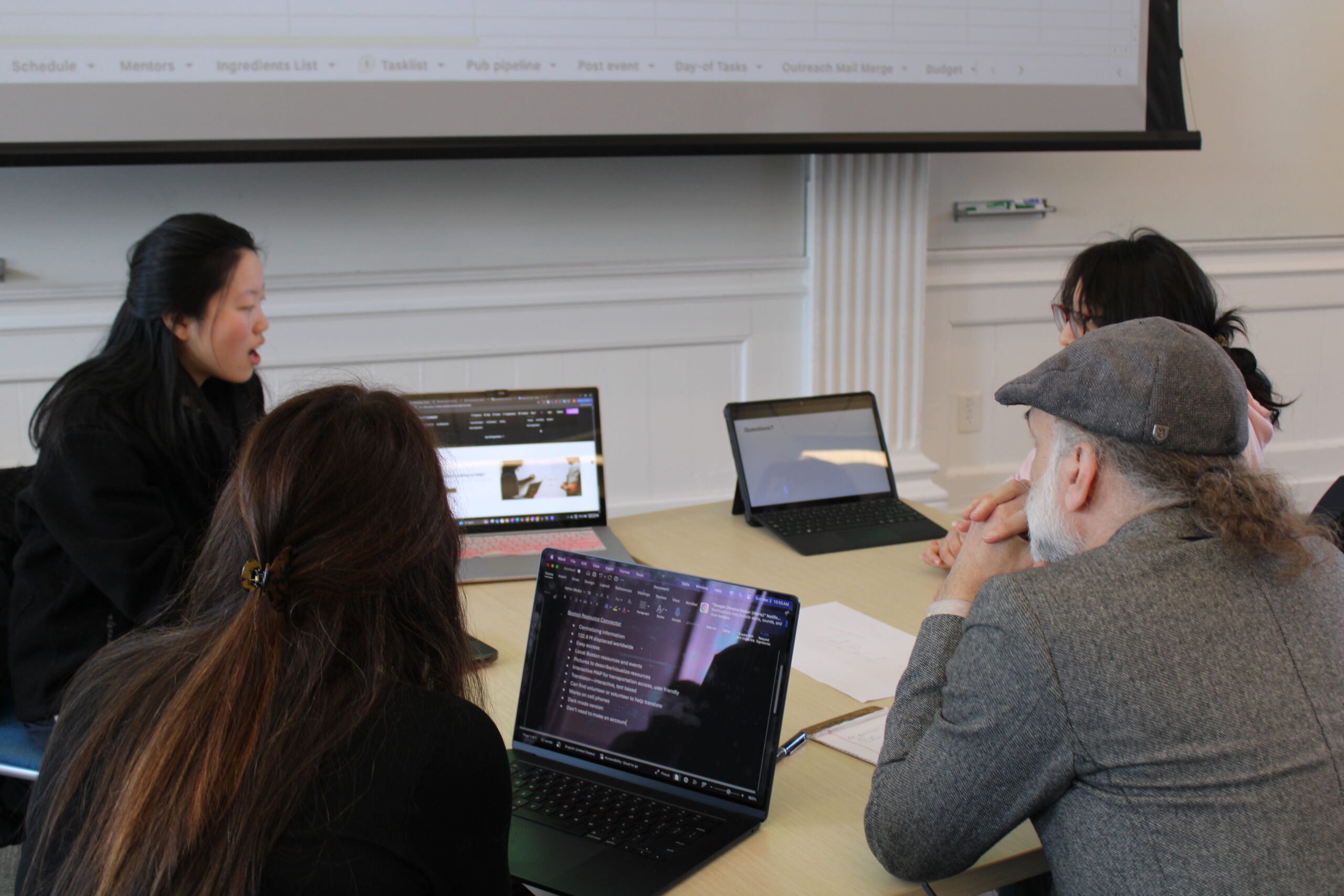

In IINE’s challenge session, Senior Vice President and Chief Advancement Officer Xan Weber provided an overview of the current displacement crises and IINE’s history and services. She outlined persistent obstacles faced by new arrivals, including language barriers, lack of transportation, affordable housing scarcity, and limited access to physical and mental healthcare. Then she moved through the challenges of this moment: the slashing of federal funding and support, roll-back of rights, and threat of mass deportation.

In IINE’s challenge session, Senior Vice President and Chief Advancement Officer Xan Weber provided an overview of the current displacement crises and IINE’s history and services. She outlined persistent obstacles faced by new arrivals, including language barriers, lack of transportation, affordable housing scarcity, and limited access to physical and mental healthcare. Then she moved through the challenges of this moment: the slashing of federal funding and support, roll-back of rights, and threat of mass deportation.  The winning pitch, offered by a team comprised of students from Harvard, Wellesley, and Tufts, was a matchmaker app to connect refugee resettlement and immigration service agencies with community volunteers and in-kind donations. Using their app, organizations would be able to create posts explaining needs, and volunteers could respond with bids to help.

The winning pitch, offered by a team comprised of students from Harvard, Wellesley, and Tufts, was a matchmaker app to connect refugee resettlement and immigration service agencies with community volunteers and in-kind donations. Using their app, organizations would be able to create posts explaining needs, and volunteers could respond with bids to help.

As arrivals increased, IINE

As arrivals increased, IINE  To further engage communities in welcoming newcomers, IINE turned back to the arts, continuing a tradition that began with its international folk festivals in the 1930s and 40s and was carried on with the Human Rights Watch Film Festival and Dreams of Freedom Museum in the early 2000s. Launched in 2017, the

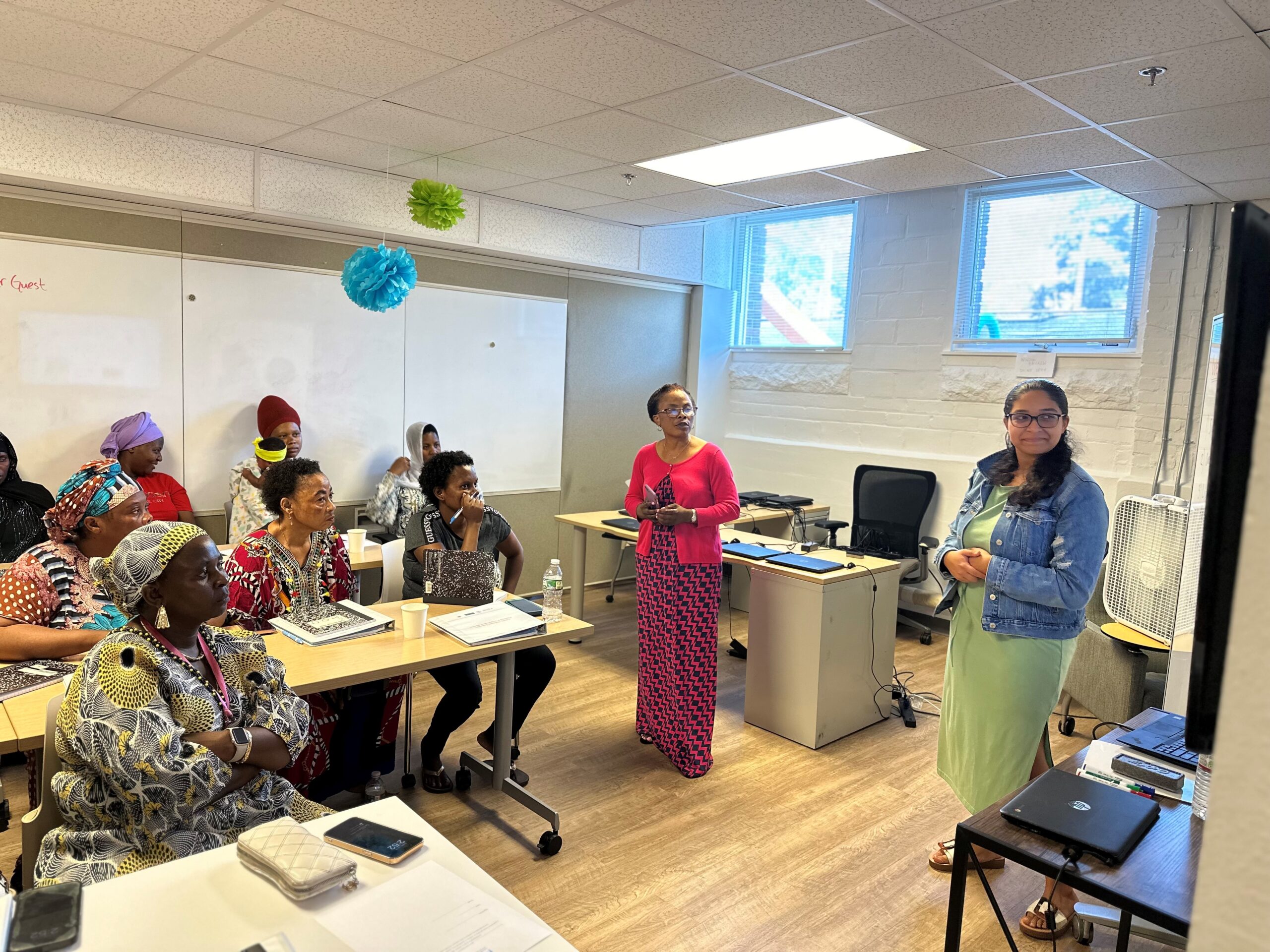

To further engage communities in welcoming newcomers, IINE turned back to the arts, continuing a tradition that began with its international folk festivals in the 1930s and 40s and was carried on with the Human Rights Watch Film Festival and Dreams of Freedom Museum in the early 2000s. Launched in 2017, the  IINE hired scores of new staff members to support Haitian arrivals, many of them Haitian, and held all-day “clinics” in its offices, and in libraries and churches, to help newly arrived families access cash assistance and immigration legal support. Public events like official city Flag Raisings on Haitian Independence Day helped rally community members to support their new neighbors. A new IINE department of Shelter Services was assembled to help clients exit state-run emergency shelters quickly, safely, and permanently.

IINE hired scores of new staff members to support Haitian arrivals, many of them Haitian, and held all-day “clinics” in its offices, and in libraries and churches, to help newly arrived families access cash assistance and immigration legal support. Public events like official city Flag Raisings on Haitian Independence Day helped rally community members to support their new neighbors. A new IINE department of Shelter Services was assembled to help clients exit state-run emergency shelters quickly, safely, and permanently.

Back in his native Haiti, Styve taught high school mathematics and statistics for eight years. The work felt important—but as

Back in his native Haiti, Styve taught high school mathematics and statistics for eight years. The work felt important—but as

In 2005,

In 2005,